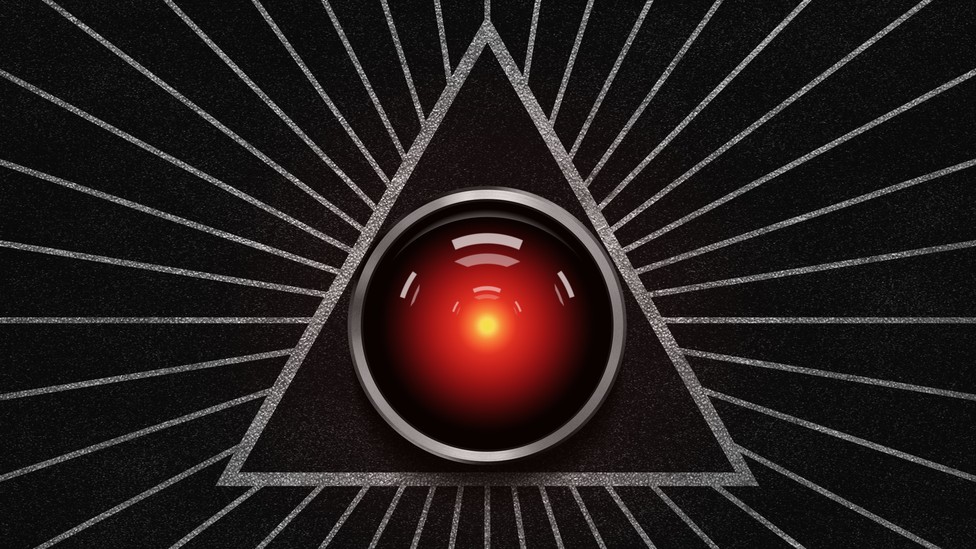

Three years ago, at a conference on transatlantic issues, the subject of artificial intelligence appeared on the agenda. I was on the verge of skipping that session—it lay outside my usual concerns—but the beginning of the presentation held me in my seat.

The speaker described the workings of a computer program that would soon challenge international champions in the game Go. I was amazed that a computer could master Go, which is more complex than chess. In it, each player deploys 180 or 181 pieces (depending on which color he or she chooses), placed alternately on an initially empty board; victory goes to the side that, by making better strategic decisions, immobilizes his or her opponent by more effectively controlling territory.

The speaker insisted that this ability could not be preprogrammed. His machine, he said, learned to master Go by training itself through practice. Given Go’s basic rules, the computer played innumerable games against itself, learning from its mistakes and refining its algorithms accordingly. In the process, it exceeded the skills of its human mentors. And indeed, in the months following the speech, an AI program named AlphaGo would decisively defeat the world’s greatest Go players.

As I listened to the speaker celebrate this technical progress, my experience as a historian and occasional practicing statesman gave me pause. What would be the impact on history of self-learning machines—machines that acquired knowledge by processes particular to themselves, and applied that knowledge to ends for which there may be no category of human understanding? Would these machines learn to communicate with one another? How would choices be made among emerging options? Was it possible that human history might go the way of the Incas, faced with a Spanish culture incomprehensible and even awe-inspiring to them? Were we at the edge of a new phase of human history?

Read the rest of this article at: The Atlantic

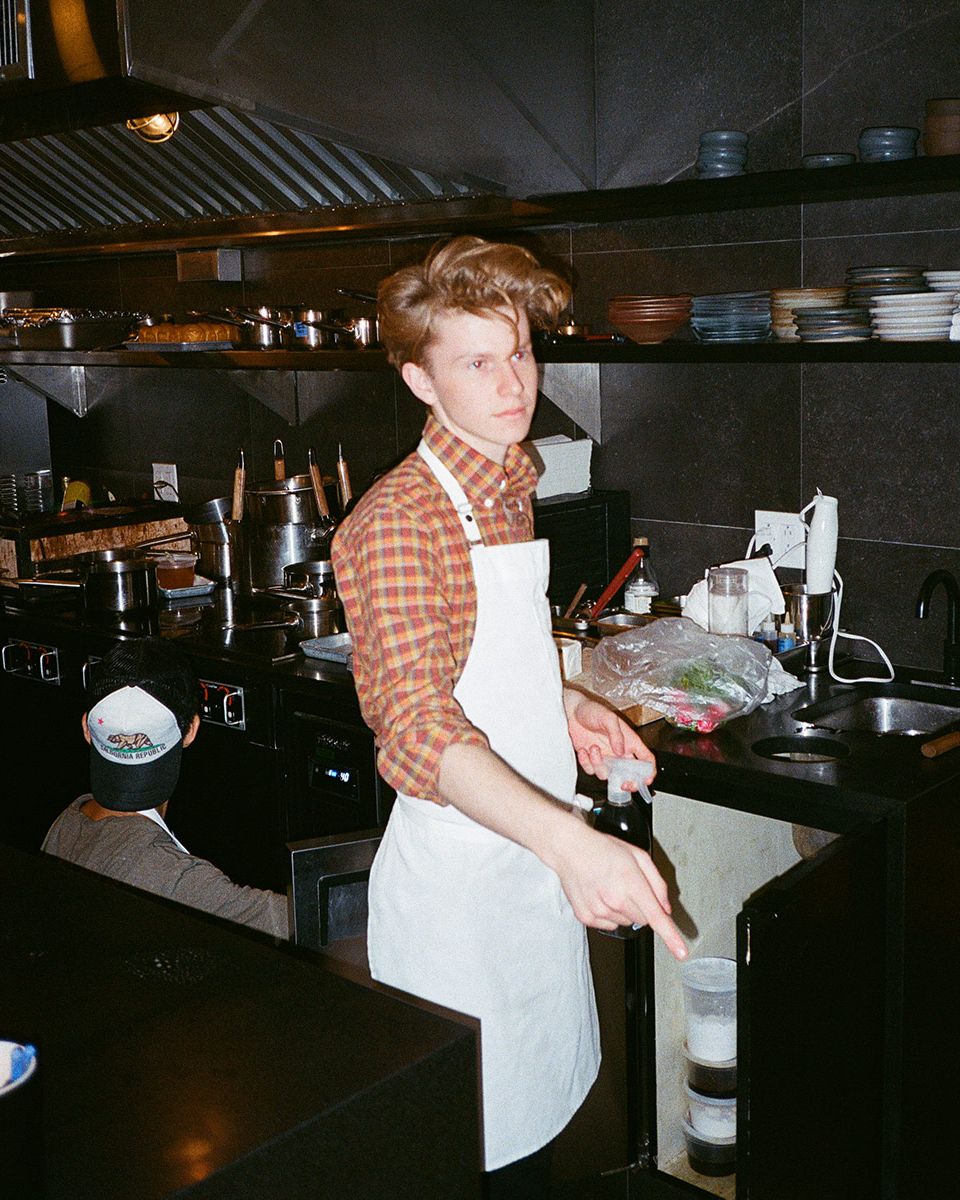

Chef Flynn McGarry knows what he likes and what he does not like. He likes very small drinking glasses (“it feels like you’re accomplishing something”). He likes good tailoring. He likes JFK (the president, not the airport), and the city of Copenhagen, and Sara Delano Roosevelt Park (“I’ve never seen a park that literally has barbed wire in it!”). What he does not like, I have just learned, is the word casual. We are at the Four Horsemen, James Murphy’s Brooklyn wine bar, eating melty little rounds of hanger steak with grilled asparagus in orange romesco pools. It’s the kind of relaxed, drop-in-when-you-feel-like-it, blond-wood-tabled restaurant that most people would call … casual. But when you describe a restaurant as casual, McGarry tries to tell me, what you are really doing is describing something else.

“To me, a casual place, you don’t get incredible service but that’s fine, because it’s casual,” he says, carefully, giving the impression that this is something he thinks about a lot. “The food comes out a little late, but it’s fine, because it’s casual. The chairs are uncomfortable and the space is too loud, but that’s fine, because the restaurant is casual.” What really offends him is the idea of using casual as an excuse for mediocrity: “I think it’s this weird situation where things that are nice are being degraded because they’re too formal.”

Read the rest of this article at: Grub Street

Has Wine Gone Bad?

If you were lucky enough to dine at Noma, in Copenhagen, in 2011 – which had just been crowned as the “best restaurant in the world” – you might have been served one of its signature dishes: a single, raw, razor clam from the North Sea, in a foaming pool of aqueous parsley, topped with a dusting of horseradish snow. It was a technical and conceptual marvel intended to evoke the harsh Nordic coastline in winter.

But almost more remarkable than the dish itself was the drink that accompanied it: a glass of cloudy, noticeably sour white wine from a virtually unknown vineyard in France’s Loire Valley, which was available at the time for about £8 a bottle. It was certainly an odd choice for a £300 menu. This was a so-called natural wine – made without any pesticides, chemicals or preservatives – the product of a movement that has triggered the biggest conflict in the world of wine for a generation.

The rise of natural wine has seen these unusual bottles become a staple at many of the world’s most acclaimed restaurants – Noma, Mugaritz in San Sebastian, Hibiscus in London – championed by sommeliers who believe that traditional wines have become too processed, and out of step with a food culture that prizes all things local. A recent study showed that 38% of wine lists in London now feature at least one organic, biodynamic or natural wine (the categories can overlap) – more than three times as many as in 2016. “Natural wines are in vogue,” reported the Times last year. “The weird and wonderful flavours will assault your senses with all sorts of wacky scents and quirky flavours.”

Read the rest of this article at: The Guardian

Consciousness is everything you experience. It is the tune stuck in your head, the sweetness of chocolate mousse, the throbbing pain of a toothache, the fierce love for your child and the bitter knowledge that eventually all feelings will end.

The origin and nature of these experiences, sometimes referred to as qualia, have been a mystery from the earliest days of antiquity right up to the present. Many modern analytic philosophers of mind, most prominently perhaps Daniel Dennett of Tufts University, find the existence of consciousness such an intolerable affront to what they believe should be a meaningless universe of matter and the void that they declare it to be an illusion. That is, they either deny that qualia exist or argue that they can never be meaningfully studied by science.

If that assertion was true, this essay would be very short. All I would need to explain is why you, I and most everybody else is so convinced that we have feelings at all. If I have a tooth abscess, however, a sophisticated argument to persuade me that my pain is delusional will not lessen its torment one iota. As I have very little sympathy for this desperate solution to the mind-body problem, I shall move on.

The majority of scholars accept consciousness as a given and seek to understand its relationship to the objective world described by science. More than a quarter of a century ago Francis Crick and I decided to set aside philosophical discussions on consciousness (which have engaged scholars since at least the time of Aristotle) and instead search for its physical footprints. What is it about a highly excitable piece of brain matter that gives rise to consciousness? Once we can understand that, we hope to get closer to solving the more fundamental problem.

We seek, in particular, the neuronal correlates of consciousness (NCC), defined as the minimal neuronal mechanisms jointly sufficient for any specific conscious experience. What must happen in your brain for you to experience a toothache, for example? Must some nerve cells vibrate at some magical frequency? Do some special “consciousness neurons” have to be activated? In which brain regions would these cells be located?

Read the rest of this article at: Nature