Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction is organized by The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Kunsthaus Zürich

FRANCIS PICABIA (French, 1879–1953) Udnie (Jeune fille américaine; danse) (Udnie [Young American Girl; Dance]) 1913 Oil on canvas 114 3/16 x 118 1/8″ (290 x 300 cm) Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle, Paris. Purchase of the State, 1948

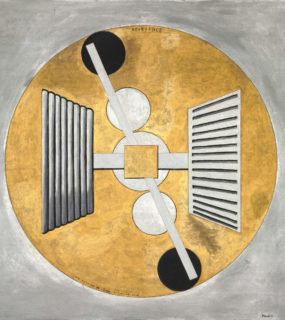

FRANCIS PICABIA (French, 1879–1953) Edtaonisl (ecclésiastique) (Edtaonisl [Ecclesiastic]) 1913 Oil and metallic paint on canvas 118 1/4 × 118 3/4″ (300.4 × 300.7 cm) The Art Institute of Chicago. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Armand Bartos, 1953

“Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction” at the Museum of Modern Art brings together more than 200 works done between 1905 and 1952—mainly paintings and drawings but also a film and related set designs—that may cause whiplash as you follow the artist’s snaking turns.

The galleries chronicle his successive reinventions: Impressionist, Cubist, Dadaist, Surrealist, Expressive Realist, Kitschy Realist, Abstract Fantasist. No style was so sacred for Picabia that he didn’t want to violate its tenets.

The show’s curators, Anne Umland of MoMA and Cathérine Hug of Kunsthaus Zürich, want us to admire his audacity rather than any set of masterworks. Their straightforward but subtle installation nonetheless suggests that, despite his zigzags, Picabia never tired of certain themes.

Read the rest of this review at the Wall Street Journal

Make way for Francis Picabia, one of the grandest, most mordant exemplars of early modernism, and perhaps the least familiar. The Museum of Modern Art — having for decades drummed the artistic feats of Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian and Duchamp into cultural consciousness — has finally rolled out the red carpet for this capricious, prolific, subversive fellow traveler.

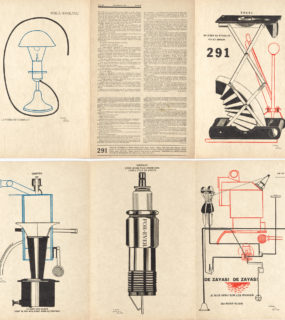

The Modern didn’t even acquire a Picabia painting until 1954, and this is its first substantial exhibition devoted to him. One imagines that the artist was too slippery or contradictory for the museum, too much of a prankster and publicity hound. Born to wealth, he never struggled as an artist and had a reputation, partly intended, as a playboy. He made important contributions to both Cubist painting and its nemesis, Dada, with its art-barbed hijinks, and refused to cultivate a personal style that deepened with time. Instead he toyed with kitsch and calendar art, and based paintings on found photographs. When he returned to abstraction at the end of his life, he tried several styles. But lately — when multiple mediums and styles are increasingly the artistic norm — Picabia’s stature has grown. His work seems more alive today than that of any artist of his cohort, even Duchamp.

Read the rest of this review at the New York Times

A self-proclaimed “Funny Guy” and “artist of many genres,” Francis Picabia was born in Paris in 1879. His father was a Cuban-born Spaniard; his mother was French. He embraced this mixed lineage and occasionally extended it, declaring, “I was born in Paris to a Cuban, Spanish, French, Italian, American family, and . . . I have the very clear impression of being all these nationalities at once!” Picabia is an artist with a strong New York connection. It was in this city that he first achieved fame as a leader of the European avant-garde. Today he is best known as an irreverent Dadaist who, like no other artist before him, created a body of work that defies consistency and categorization, ranging as it does from Impressionist landscapes to abstraction, from paintings of machines to photo-based nudes, and from performance and film to poetry and publishing. Picabia lived through the devastation of two world wars, which fueled his persistent nihilism and profound sense of the absurd. It is against this backdrop of repeated historical trauma that his aversion to rational thinking and fixed positions—whether national, political, social, or cultural—and his ongoing shapeshifting are best understood. “Our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction” is an aphorism Picabia coined in 1922. It encapsulates the nonlinear character of his five-decade career. This exhibition is the first in the United States to present that career in full, with the aim of advancing appreciation of Picabia’s unruly genius and its vital place in the history of modern art.

Read more at the MOMA